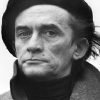

The author on himself

Photographer unknown

I looked up to him [my father], he helped me solve problems. I would turn to him in matters of exceptional necessity. My father’s lifestyle and reluctance to impose would create a sort of barrier between him and other people, even his son. I sensed that he suffered because no one had the courage to approach him. My father was my teacher in many fields, but always in the spiritual and intellectual sphere. He was not adapted to fighting for survival in everyday life; he found it hard to accept the practical side of the surrounding reality. Though father read my first poems, it was my sister who told me that he liked them. Thanks to that I started to have a little confidence in myself. He was not aware and never found out how important his opinion was for me.

But you should know that, before […] I developed any interest in literature, I was interested only in entomology! […] There is a mysterious link between Leśmian and entomology. Znikomek, Śnigrobek and Srebroń are all cousins of bumble bees and various beetles, which also appear in his poems. Leśmian’s creations are akin to God’s creations, they are similar species, related even by name. I don’t know which Leśmian it was that once bustled around Polish entomology and gave butterflies and moths such homely sounding names. These are all neologisms in the spirit of Leśmian: zmrocznik, nastrosz, zmierzchnica, powszelatka, przegibek, zasmutek, marzymłódka, pokłonnik… And Leśmian himself, with his poetic name, is a member of this family.

Poetry is a sacral practice. For me, it is the only opportunity of metaphysical creation outside the system of faiths and cults, outside religious practices involving active intercourse with the sacrum. Is it the crowning achievement in the craft, the result of mastering its rules? Maybe, but I don’t feel it. When I start to write, and I do it with anxiety, I always feel like a debutante starting over once again, starting from scratch. I always have a barely perceptible impression that I’m not creating anything new, but merely reproducing, cracking a code that has not been deciphered yet. Does that sound “solemn and murky”? If it does, it’s because I myself find those things unclear and mysterious.

Because this [the suffering of Jewish people] is my great guilt. The guilt of all those who survived. This is how I feel it, please put this guilt in inverted commas. Please do not take it literally. It is not my sin or my guilt in a literal sense or, even less so, my wrongdoing. But I feel that if I was destined to survive, this means that I am guilty.

I am above all a poet, or actually, exclusively a poet, all the rest is an addition, an important one, but an addition, scraping up experiences. I have already accepted the fact that I am most readily seen through this lens. And when someone asks me about poetry, about my poems, they often ask me why I am not there, why I camouflage myself and hide. But I am there openly and exclusively. There is a kind of autobiographical essence in those poems, they are not tales. They are my “very real” memoirs, I will not write differently.

Photo by Jerzy Ficowski

There was a Mr Stanisław Gilowski in Jarosław before the war. His phone number was 225 (I got his number from the 1932-33 Polish national telephone directory). I read with admiration and disbelief: the owner of the Uciecha cinema, a steam bath, a soda factory and a funeral parlour. Am I as multi-faceted and versatile as he was? I must confess (from the depths of my belief) that I’m only seemingly as versatile as the unsurpassed Gilowski, but all those versatilities and multiplicities of mine actually stem from one common root and eventually merge into one. How? This is not a question for me to answer.

Most of the texts quoted here can be found in a collection entitled Wcielenia Jerzego Ficowskiego. Reviews, sketches and interviews from the years 1956-2007, selected and edited by Piotr Sommer, with a foreword by Piotr Sommer, Pogranicze Sejny 2010. While some of these texts were subsequently reprinted, only the first publication dates have been stated above.