References

Photographer unknown

I would rank Ficowski’s Moje strony świata alongside Herbert’s Hermes, pies i gwiazda, also published in 1957, a prolific year for poets.

The property that Sandauer would call “peripherality”, and which he discovered in Białoszewski’s writing, also plays an important part here [in Moje strony świata J.F.]. This similarity of otherwise so dissimilar poets has something peculiar, and yet almost regular about it: there, in a tiny room or apartment, amidst tightly packed furniture, was the last stand of man and poetry.

What he has laboriously put together, he presents with the grace and accuracy of a poet. Because there is nothing a true poet can stand less than randomness and ambiguity.

In his translations, Ficowski managed to achieve some unity of poetic style. Thanks to that, works that differ so much in mood and subject matter, and display attitudes that apparently come from the opposite poles of the Polish Jews’ culture […] all seem a part of some community of poetic language and culture. […] Finding such an original formula of poetic style in this kind of anthology is probably the greatest artistic achievement.

A superb translator of Lorca, the discoverer of Papusza, defender of Polish Gypsies’ culture and rights, who has long deserved the title of their envoy. He was one of the pioneers of our current knowledge of Schulz in the post-war period, a time when no one would yet dream of the possibility of reviving this long-forgotten prose. Copies of Schulz’s work discovered by Ficowski were the first to be broadly circulated in Warsaw nearly twenty years ago. Ficowski’s poetry is protected from all sides by a coat of the rarest and noblest passions, which the author has pursued with the infinite patience of a researcher and, I believe, also with that dose of amusement that a poet must experience when trying on masks of a learned erudite. And yet, those passions were always at odds with the common trends.

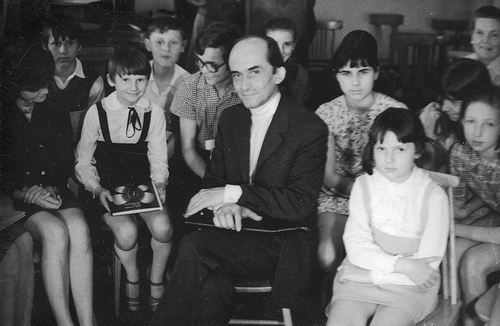

With Alfred Schrayer in Drohobycz, 1988 (in the background – Mazepy Street, formerly Stryjska, the prototype of Schulz’s “Street of Crocodiles”), photographer unknown

Like most contemporary poets, Ficowski has a clear penchant for language’s poetic alchemy, but he is not like those fanatic extremists of linguistic experimenting. For him, linguistic discoveries and experiments are almost never the goal in itself. They usually play an accessory role. The fabric of the language in his poems is always perceptible and hugely relevant, but at the same time fully transparent. It always exposes something that is already beyond the realm of the language

“What appeals to me most in Schulz is that his extraordinary literature essentially concerns the mundane, day-to-day reality, beneath which you discover something shocking and dazzlingly real,” said Ficowski about Schulz – a poet of prose. This is also what is most appealing in the writings of Ficowski, an outstanding poet turned prose writer.

I do not ask when Ficowski’s “Jewish involvement” began. The question is when the poet’s human involvement began, the involvement that would, over the years, turn into an allegorical, spiritual and emotional bonding with people condemned to cruel death only because of their “different background”. You cannot simply enter the scene at the moment of someone’s death to embrace it as your own: you cannot simply adopt someone else’s suffering, humiliation and homelessness as your own, private experience, so personal that you could write poems about it.

Regardless of success, and in spite of all success, isolated from idle discussion, unnoticeable or, rather, unnoticed things happen in poetry, and who knows whether it’s not those things that will not testify to us in the future. Testify not only to poetry, but also to the times, difficult years, denied human existences. Jerzy Ficowski’s poetry is one of the most notable phenomena in this true, but unwritten history of literature. […] Little is told about Ficowski in the “independent” press. He does not belong to the “new wave” generation of poets who take on political and moral topics and make collages of newspaper scraps. As a poet he does not belong anywhere, he is suicidally himself.

It seems to me that Ficowski’s muse is Mnemosyne, or, expressed more simply, memory. We are bitterly aware that no writing, however moving and noble, can save the world, or even a single human being. From that drawback one should arrive at a positive conclusion, that no power, no tribunal can absolve us from condemning a crime and speaking on behalf of the victims. To describe the unparalleled Nazi crime against Polish Jews is a task beyond the scope of any epic, any novel, even any documentary account. High statistics do not appeal to the imagination. In his A Reading of Ashes Ficowski has achieved something that would have seemed impossible: he has given artistically convincing shape to what cannot be embraced by words; he has restored to the faceless their human face, their individual human suffering, that is to say, their dignity. In the teeth of hypocritical indifference and a conspiracy of silence, he has once more meted out justice before the visible world.

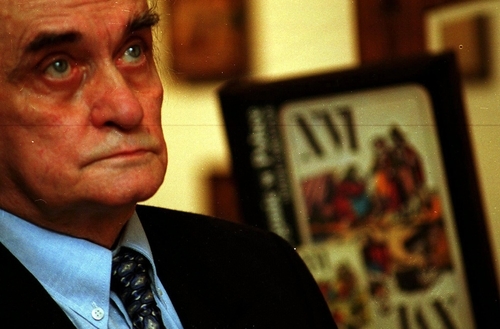

Photo by Przemysław Graf, Agencja Gazeta

With Ficowski, words always had memory, they were loaded with it. This longing to hear their mysterious echoes, magical, cabalistic murmurs and rustles, this passion for collecting lexical artefacts in the spirit of Leśmian, Tuwim, or in the more intellectual spirit of Norwid, appeared in his poetry many years ago.

Jerzy Ficowski is undeniably the best [Holocaust] poet. […] Being a poet myself, I feel admiration and I am happy that someone has been able to express so forcefully and so finely something that I think and would like to speak out myself. Ficowski’s poems are masterpieces.

Ficowski’s book [W sierocińcu świata] is also a resurrection of Wojtkiewicz’s world and a successful attempt to show his originality. The beautiful and suggestive language in which the book is written helps to develop a general artistic awareness. Ficowski has turned language into a tool for exploring beauty and devoted his poetic talent to improving the language that we use to speak about art, extending the boundaries of its adequacy. The greatest artists have achieved the same thing. It makes me think of Rilke, when he became Rodin’s secretary, of Valéry and his Degas, of Apollinaire and his cubists, but also – using a closer example – of Herbert and the Dutch painters, of Pollakówna and Czapski. Ficowski’s relationship with Wojtkiewicz seems to be of equally great importance.

The language of his poems, a language in motion, a language moving along, across and deep down, venturing into niches that it may have forgotten ever existed, or suddenly (though rather infrequently) chased by Ficowski to the limits of its capability, comes out of these trials not only as the winner, but does so with a margin that his contemporaries, otherwise a bunch of superb poets, seldom even dream of achieving. […] This language, with its oxymoronic structure, which turns everything it can inside out (exposing Ficowski’s famous “flip sides of the views”) and which quite radically upsets the hierarchies (such as with a “holy louse” facing an “empty sky”), effectively redefines the status of everything that has been named or referenced or, possibly, everything that thereby exists or has existed.

Folk storytelling, fable cross-bred with parable, anecdote mingled with fairy tale, which brings a child and an adult reader together; like the Grimms’ Fairy Tales, they are written with all naiveté and innocence. Without dilettantish rashness, but with deep affection and simplicity that always yield incredible results. The intended blends with the instinctive, refined adulthood with the poetic juvenility of a child, which Ficowski, the author of Tęcza na niedzielę and Makowskie bajki, prizes above all.

Photographer unknown

One strength of Ficowski’s poems is their ability to smite the conscience. After all, his achievements in the language of poetry would not have such a magnitude had he not proven himself in confrontation with a topic whose gravity often overruled the dilemmas of the art. While Ficowski can be placed alongside Leśmian and Białoszewski, there is yet another context to his work that deserves to be mentioned, namely, the work of Tadeusz Różewicz. Różewicz, haunted by anxiety about the moral legitimacy of post-Auschwitz poetry, had reached the limits of literature and even transgressed them, which can naturally only mean that he had moved them further. Ficowski, not less overwhelmed, remained within the bounds of literature (he is often seemingly conventional even), showing its still unexhausted potential to serve the artistic and non-artistic truth.

[J.F.’s personality] manifests itself only as much as it takes to convey the excellent and distinctive quality of the poetry he translates; a translator who is also an outstanding poet is visible in translations thanks to his inventiveness, intuition and stylistic self-awareness. But he is careful to stay hidden at all times, always wanting to show only the original and its creator, even if the latter is anonymous. A beautiful paradox: Ficowski can both exist and – as Leśmian would have put it – “unexist” in someone else’s poem.

If Schulz is a classic of Polish and world literature today, then Ficowski is the most classical of his researchers and exegetes. He does not impose his interpretation upon others – he is more like a guardian of the letter, defending the integrity of the Schulzian message against all those who would like to dumb it down, trivialise or reduce it to their own needs or ideological assumptions.

The uniqueness of Ficowski’s poetry lies not only in the diversity of the worlds it describes, but also in that it absorbs all their richness and subordinates it to the poet-director, who assigns roles and puts together a spectacle that sparkles with the wit of poetic associations, wanders between motifs and has a truly Genesical power to create worlds. It is ruled by jest and paradox, changing roles and costumes, in which the common becomes elevated and the sanctified exposes its helplessness, words obediently tell their stories and abstract concepts humbly step down to earth. All these traits of poetics and imagination (their list is by no means complete) create a nearly surreal climate that is alert to myth and tradition, and creates a sense of novelty with its means of expression.

Most of the texts quoted here can be found in a collection entitled Wcielenia Jerzego Ficowskiego (Incarnations of Jerzy Ficowski). Reviews, sketches and interviews from the years 1956-2007, selected and edited by Piotr Sommer, with a foreword by Piotr Sommer, Pogranicze Sejny 2010. Some of these texts were subsequently reprinted, but only the first publication dates have been stated above.